Comments and Views on Cases, Recent Developments and Regulatory Reforms from the Department of Law and Criminology

Company and Insolvency Law

The Crown Preference is Law (Again): Spinning the Clock Back to Early-2000s?

written by Dr. Eugenio Vaccari (Lecturer, RHUL)

The Pari Passu Principle

In corporate insolvency procedures, not all creditors are alike. This is despite the pari passu principle.

The pari passu principle is often said to be a fundamental rule of any corporate insolvency law system. It holds that, when the proceeds generated by the sale of debtor’s assets are distributed to creditors as part of an insolvency procedure, they have to be shared rateably. In other words, each creditor is entitled to a share of these proceeds that corresponds to the percentage of debt owed by the company to its creditors.

Imagine that a company has creditors for £100,000. Creditor A has a claim for £1,000, creditor B for £5,000. The company is insolvent and it is liquidated. The sale generates £50,000 of proceeds available to be distributed to the creditors. While it would have been possible to say that, for instance, older creditors or creditors with larger claims are paid first, the pari passsu principle states that all creditors are treated alike. As a result, creditor A will receive 1% of these proceeds (£500), while creditor B will receive 5% of them (£2,500).

There are, of course, exceptions to the pari passu principle.

First, the pari passu principle applies only to assets that are available for distribution. For instance, a bank may have granted a mortgage to the debtor to buy a property, and the debtor may have given that property as a collateral to the bank. If the debtor becomes insolvent, the proceeds generated by the sale of that property are distributed first to the bank and then, if anything is left, to the other creditors.

Secondly, the law might introduce exceptions to this principle, in order to prioritise the payment to creditors that are deemed particularly worthy of additional protection.

The Law

Until the Enterprise Act 2002, the Inland Revenue and HM Customs & Excise (now HMRC) were granted a status as preferential creditors for certain debts listed in Schedule 6 of the Insolvency Act 1986. As a result, debts owed to the them had to be fully paid before any distribution to floating charge holders, pension schemes and unsecured creditors (among others) was made.

This preferential status granted these agencies a stream of £60-90 million each year in insolvencies. Section 251 of the Enterprise Act 2002, however, abolished the Crown’s status as preferential creditor and introduced a new regime (the ‘prescribed part’) wherein a portion of the distributions in liquidation was ring-fenced specifically for unsecured creditors.

Back in the 2018 Budget, mixed in with many other tweaks, the Government announced a seemingly innocuous change to the way in which business insolvencies will be handled from 6 April 2020 (later postponed to insolvencies commencing on or after 1 December 2020, irrespective of the date that the tax debts were incurred or the date of the qualifying floating charge).

Without attracting much publicity, the announced move was codified in sections 98 and 99 of the Finance Act 2020, which received Royal Assent on 22nd of July 2020. As a result, HMRC gained secondary preferential treatment over non-preferential and floating charge holders – often banks that have loaned money to firms – for uncapped amounts of VAT, Pay As You Earn (‘PAYE’) income tax, student loan repayments, employee National Insurance Contributions (‘NICs’) or construction industry scheme deductions.

In a related development, Parliament also approved the Insolvency Act 1986 (Prescribed Part) (Amendment) Order 2020. The effect of this Act is to increase the prescribed part from £600,000 to £800,000. However, this change does not apply to floating charges created before 6 April 2020.

So What?

The Government argue that giving HMRC priority for collecting taxes paid by employees and customers to companies is appropriate. These represent taxes that are paid by citizens with the full expectation that they are used to fund public services. Absent any form of priority, this money actually gets distributed to creditors instead. As a result, the Exchequer should move ahead of others in the pecking order and give HMRC a better chance of reclaiming the £185m per year they lose.

These explanations do not appear totally sound. The creation of the prescribed part and the increase of its cap to £800,000 served the purpose of ensuring that at least some of this money is paid back to the HMRC and used to fund public services. What has not been properly considered is the impact the Crown preference and the increased prescribed part will have on: (i) the wider lending market and access to finance; as well as (ii) corporate rescue practices.

With reference to lending practices, the new system disproportionately affects floating charge holders and unsecured creditors. The abolition of administrative receivership – a procedure controlled by lenders – by the Enterprise Act 2002 was compensated by the loss of preferential status for the HMRC. The re-introduction of such preference means that lenders in general and floating charge holders in particular will be pushed to lend money at higher interest rates, as lenders have no idea as to the tax arrears of any borrower on a day-to-day basis.

Lenders now face a double blow (increased prescribed part and Crown preference) in relation to realisations from the floating charge. They are, therefore, likely to reduce the amounts that they lend to businesses, to take account of the dilution in the realisations that they would receive in insolvency. This is a particularly unwelcome outcome in the current marketplace.

Lenders are even more likely to seek fixed charge (where possible) and to introduce covenants for reviewing the debtor’s tax liabilities. Such liabilities are likely to increase significantly in the next few months, as VAT payments due by businesses between March and June 2020 have been deferred until the end of the 2020/21 tax year. Lenders may also insist that a borrower holds tax reserves to deal with liabilities to HMRC and, in large operations, on group structures which minimise the dilution from Crown preference.

Finally, unsecured creditors may choose to protect themselves by keeping their payment terms as tight as possible and limiting the number of days that credit is offered for.

Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, such move may hamper the willingness to support an enterprise and rescue culture, which was the main justification for the abolition of the Crown’s preference. This is because HMRC’s gain is the other creditors’ loss, especially considering that the taxes classified under the preferential claim are ‘uncapped’ (while before the enactment of the Enterprise Act 2002 they were capped to amounts due to up to 1 year before the commencement of the procedure).

Despite assurances to the contrary, the existence of a preferential treatment may push the HMRC to exercise increased control over the insolvency process and promote early petitions for liquidation in the hope of higher return.

Also, the HMRC has never historically been particularly supportive of reorganisation efforts. This means that distressed companies may have to file for a new restructuring plan under part 26A of the Companies Act 2006 and seek a court-approved cross-class cram-down to overcome the HMRC’s negative vote. Such an approach would increase cost, litigation and time needed for the reorganisation effort, thus potentially pushing viable debtors out of business.

There are other elements that militate against the re-introduction of such preferential status. HMRC currently have the ability to robustly manage their debt. HMRC have powers not available to other unsecured creditors, including the ability to take enforcement action without a court order to seize assets and to deduct amounts directly from bank accounts.

HMRC have the power to issue Personal Liability Notices to corporate officers for a failure to pay National Insurance Contributions (NICs) or future unpaid payroll taxes. HMRC also have the power to insist on upfront security deposits where there is a genuine risk of non-payment of PAYE, NICs or Value Added Tax (VAT). Similarly, HMRC may issue Accelerated Payment Notices for disputed tax debts.

One of the key features of the English corporate insolvency framework is its focus on promoting business rescue and, more in general, a rescue culture, as evidenced in previous papers[1] by the author of this post. The recent long-term changes introduced by the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 seemed to go in the direction of strengthening the rescue attitude. It makes, therefore, little sense to introduce policies designed to help businesses survive the Covid-19 pandemic and, at the same time, reduce their ability to borrow cheaply. The re-introduction of the preferential status for certain unpaid taxes spins the clock back to 2003 and is likely to hurt the existing, fragile business recovery.

[1] E Vaccari ‘English Pre-Packaged Corporate Rescue Procedures: Is there a Case for Propping Industry Self-Regulation and Industry-Led Measures such as the Pre-Pack Pool?’ (2020) 31(3) I.C.C.L.R. 169; E Vaccari, ‘Corporate Insolvency Reforms in England: Rescuing a “Broken Bench”? A Critical Analysis of Light Touch Administrations and New Restructuring Plans’ (2020) 31(12) I.C.C.L.R. 645; E Vaccari, ‘The New ‘Alert Procedure’ in Italy: Regarder au-delà du modèle français?’ (2020) 30(1) I.I.R. 1.

This blog was first published here on 6 August 2020.

Pre-packaged Administrations in the UK: Nothing New under the Sun?

written by Dr. Eugenio Vaccari (Lecturer, RHUL)

Published on 2 February 2021

The English corporate insolvency framework has gone through significant changes in recent times. Some of these changes have been introduced as soon as the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the UK economy became apparent. Nevertheless, last summer the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 (the Act), which completed its progress in the Parliament and received Royal Assent on 25 June 2020, coupled these temporary measures with long-term reforms and regulatory powers to significantly amend the UK corporate insolvency framework.

Similar to other countries, the UK introduced some emergency legislation aimed at suspending statutory demands and restricting winging-up petitions,[1] as well as the liability for wrongful trading.[2] At the same time, with the Act, Parliament took the opportunity to introduce some long-discussed and more permanent changes to the corporate insolvency framework. These include the introduction of a short free-standing company moratorium,[3] a new restructuring plan procedure (known as “part 26A restructuring plan”) modelled after the successful schemes of arrangement (but with a cross-class cram-down!),[4] and a general ban on the enforceability of ipso facto clauses.[5]

It seems, therefore, that the country – or at least its legislator – is trying to replace or, at least, discourage the use of the formal insolvency procedure originally designed to promote the rescue of distressed yet viable companies. This is the administration procedure governed by Schedule B1 of the Insolvency Act 1986, as amended by the Enterprise Act 2002.

There is, in fact, a widespread belief that this procedure is inadequate to achieve the goals for which it was introduced. These are: rescuing the company as a going concern, achieving a better result than liquidation or, in the last instance, realising the company’s assets to make a distribution.[6] For instance, media outlets frequently depict administration as “the end of the road” for the debtors by reporting on companies “collapsing” into administration.[7]

To be fair, for some companies, administration is the end of the road. This seems to be the case of one of the most illustrious administration cases of this year, Philip Green’s Arcadia group collapse into administration.[8] In the case of Arcadia, it is quite likely that the doors of the stores of the retail group will never open again. Its most iconic brands are being sold to online retailers,[9] and the company’s 13,000 employees are going to be jobless in the next few weeks.

However, it appears a bit too premature to call for the demise of administration as a valid and efficient tool for rescuing companies and/or turning around their business. This opinion seems to be shared by Parliament which, back in June 2020, granted to the Government an extension to end of June 2021 to the power to legislate on pre-packaged sales to connected persons. This legislative power was originally granted by the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 but later expired in May 2020.[10]

At the time of writing, it seems that the Government is willing to legislate in the area before the extended deadline expires. In fact, on 8 October 2020, the UK Government published draft regulations[11] aimed at pre-packaged sales to connected parties which occur by means of an administration proceeding. The term ‘pre-packaged sale’ refers to an arrangement under which the sale of all or part of a company’s business or assets is negotiated with a purchaser prior to the appointment of an administrator and the administrator effects the sale immediately on, or shortly after, appointment.[12]

According to the legislative proposal, where an administrator wishes to dispose of all or a substantial part of a company’s assets within the first eight weeks of the administration to one or more connected persons, then the administrator will need to obtain the creditors’ approval or an independent written opinion by an 'evaluator'. This written opinion will be made available to the creditors and a copy will need to be filed at Companies House.

The provider of the opinion (referred to in the regulations as the ‘evaluator’) must be independent of the connected party purchaser, the company and the administrator, and must meet certain eligibility requirements. In the past, such opinions were provided by an independent body of business experts known as the ‘Pre-Pack Pool’ (‘the Pool’).[13] However, the Pool has so far suffered from a low uptake rate of referrals, mainly due to the voluntary nature of such referrals by the connected party purchaser. Additionally, the Pool has wrongly been perceived as inadequate to identify bad deals. This bad publicity primarily generated from the unfair reports on the Polestar case, where the pre-pack sale fell through for reasons that had nothing to do with the “positive” opinion[14] on the pre-pack sale given by the Pool.[15]

It seems, therefore, unlikely that the Government will rely solely on the Pool for this role. In fact, section 9 of the draft regulations refers to the evaluator as “an individual”, not as a body of experts. Nevertheless, nothing seems to suggest that evaluators could not join independent bodies in order to gain visibility and promote their services on the market. The Pool may, therefore, end up in being one of the evaluators, rather than the only one (as it is the situation today).

It is clear that with these draft regulations, the Government is trying to introduce additional checks and balances in an area where there is a widespread perception of abusive or at least strategic behaviour from businesses. In particular, the Government is concerned that these practices could result in mechanisms to avoid tax and pension liabilities.[16]

It is arguable whether the negative perception around pre-packs, and especially those to connected parties, always reflects the reality. The author is not aware of any recent empirical studies, which suggest an increased use of pre-packs in a strategic or abusive manner. At least, in this context, it is reassuring that the Government, through its Insolvency Service, has not chosen to completely ban pre-packs (despite having such power in light of the Act). It is encouraging that the Government has recognised that pre-packaged sales in administration are a valuable rescue tool in the restructuring toolbox, especially in the current economic and financial situation. For instance, just a few days ago, Paperchase was successfully rescued in a pre-pack deal to a connected party (Permira Debt Managers, an investor in Paperchase since 2015), thus safeguarding around 1,000 jobs in the hard-hit retail sector.[17]

It is questionable whether and to what extent the draft regulations will address the concerns they are designed to alleviate. Their scope may be too broad and there is little clarity on the potential liability of the evaluator in case of perceived mistake (see the Polestar case). With reference to the qualifying criteria to be an evaluator, these have proved particularly controversial in the industry, with some believing that they could open the door to abuse of the system.[18]

It is not clear on which basis the creditors’ opinion could be independently formed in the absence of a report from the evaluator. Additionally, it seems unlikely that creditors will be frequently asked to validate a pre-pack deal, as at least 14 days prior notice is required for their approval. This rather lengthy notice period – if not amended in the final version of the law - jeopardises the main benefits (speed and efficiency) associated with pre-pack sales.

Finally, while the administrator could in theory ignore the evaluator’s opinion, it is difficult to see how an officer of the court could act against the advice of an independent expert. Furthermore, the position of secured creditors in these deals need to receive further attention. A note within the government's report suggests that pre-pack sales to a secured lender to the company will not be caught by the regulations. However, the draft regulations do not expressly include any such exemption at this time.

Nevertheless, this draft legislation seems to strike a balance between the interests of the parties involved in a sale, as well as promote transparency and disclosure in potentially murky deals. It is essential that the newly proposed mechanisms do not result in additional costs and delays for the parties of the proposed deals. At the risk of stating the obvious, it is worth remembering that time and money are of the essence for all companies, but particularly those finding themselves in a situation of financial distress.

[1] Sections 10-11 of the Act.

[2] Sections 12-13 of the Act.

[3] Sections 1-6 of the Act.

[4] Schedule 9 of the Act.

[5] Sections 14-19 of the Act.

[6] Paragraph 3, Schedule B1 IA 1986.

[7] By way of example, see: S Butler, ‘Carluccio’s and BrightHouse collapse into administration’ (The Guardian, 30 March 2020) <https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/apr/14/oasis-and-warehouse-close-to-collapsing-into-administration-coronavirus>; S Butler, ‘Oasis and Warehouse close to collapsing into administration’ (The Guardian, 14 April 2020) <https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/apr/14/oasis-and-warehouse-close-to-collapsing-into-administration-coronavirus>; S Butler, ‘Peacocks and Jaeger businesses collapse into administration’ (The Guardian, 19 November 2020) <https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/nov/19/peacocks-and-jaeger-collapse-into-administration-4800-jobs>, all accessed on 2 February 2021.

[8] S Butler and J Partridge, ‘Philip Green’s Arcadia Group collapses into administration’ (The Guardian, 30 November 2020) <https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/nov/30/philip-green-arcadia-group-collapses-into-administration> accessed 2 February 2021.

[9] M Sweney and Z Wood, ‘Bohoo in talks to buy Dorothy Perkins, Wallis and Burton’ (The Guardian, 29 January 2021) <https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/jan/29/boohoo-in-talks-to-buy-dorothy-perkins-wallis-and-burton-arcadia>; K Makortoff, ‘Asos buys Topshop and Miss Selfridge brands for £330m’ (The Guardian, 1 February 2021) <https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/feb/01/asos-buys-topshop-topman-miss-selfridge-arcadia>, both accessed 2 February 2021.

[10] Section 8 of the Act.

[11] Draft Administration (Restrictions on Disposal etc. to Connected Persons) Regulations 2020 <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pre-pack-sales-in-administration> accessed 2 February 2021.

[12] Statement of Insolvency Practice 16.

[13] < https://www.prepackpool.co.uk/>.

[14] In reality, the Pool does not state if the sale should go through. It only states if the case for a sale to a connected party is not unreasonable, unreasonable or if additional evidence is needed.

[15] J Francis, ‘Polestar sites go into administration’ (Printweek, 25 April 2016) <https://www.printweek.com/news/article/polestar-sites-go-into-administration> accessed 2 February 2021.

[16] L Haddou and J Cumbo, ‘Companies use ‘pre-packs’ to dump £3.8bn of pension liabilities’ (Financial Times, 9 April 2017) <https://www.ft.com/content/f3f574fa-0f2c-11e7-a88c-50ba212dce4d> accessed 2 February 2021.

[17] J Bourke, ‘Paperchase to keep majority of its shops open, safeguarding around 1,000 jobs’ (Evening Standard, 29 January 2021) <https://www.standard.co.uk/business/leisure-retail/paperchase-prepack-administration-b908314.html> accessed 2 February 2021.

[18] J Hillman, ‘Compulsory independent scrutiny of pre-pack sales to connected parties’ (Pinsent Masons, 22 October 2020) <https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/analysis/compulsory-independent-scrutiny-pre-pack-sales-connected-parties> accessed 2 February 2021.

The Pension Regulator’s New Powers: A Major Constraint to Corporate Restructuring?

written by Dr. Eugenio Vaccari (Lecturer, RHUL)

Published on 21 February 2021

Introduction

The Pension Schemes Act 2021 received Royal Assent on 11 February 2021. It brings with it many changes to the Pensions Act 2004 affecting pension scheme trustees, employers, and advisers. Some of these changes also affect insolvency practice. This article tries to clarify the consequences of the Pension Schemes Act 2021 for corporate insolvency practice.

Pension Schemes

There are two main types of private pensions in the UK. More recently, employers have moved towards defined contribution (DC) pension schemes. In DC pension schemes, workers contribute with part of their salaries to a workplace or private pension through their employers. These contributions are usually made on a monthly basis. The money is put into investment by the pension provider and the value of the employee’s pension varies depending on the performance of such investment. The return to the worker depends on how much was paid in the scheme and on the performance of the investment.

The employer’s liquidation or administration is unlikely to affect DC schemes, provided that contributions remained current throughout the employment. The scheme is independent from the employer. Unpaid employment contributions can be claimed from the National Insurance Fund. If the pension provided which runs the scheme enters into a formal insolvency proceeding, the worker can seek compensation from the Financial Services Compensation Scheme.

The traditional type of private pension, however, has always been the defined benefit (DB) pension scheme. A DB pension (also called a “final salary” pension) is a type of workplace pension that pays a retirement income based on the salary and the number of years the employee has worked for the employer. It is irrelevant the amount of money the worker contributed to the pension. Nowadays, most private sector DB pension schemes are closed to new members and/or new accruals. However, DB pension schemes remain an integral part of the UK pensions system, with an estimated 10.4 million members relying on them.[1]

Shortfalls in DB pension schemes are far from uncommon. According to the latest figures available on the PwC’s Skyval index,[2] the funding deficit for the UK’s 5,000-plus corporate DB pension schemes was in the region £120 billion in January 2021.

On a company’s insolvency, the DB pension scheme is protected by the industry lifeboat fund run by the Pension Protection Fund (PPF).[3] Created by the Pensions Act 2004, the PPF is an insurance arrangement and a statutory public corporation accountable to Parliament through the Secretary of State for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). The Government is clearly interested in reducing the instances in which the PPF is called to rescue an insolvent DB pension scheme.

TPR Regulatory Powers

The Pension Regulator (TPR) is the body that regulates work-based pension schemes. It became operational on 6 April 2005. One of its goals is to hold directors and shareholders accountable for imbalances in the pension schemes. To achieve this goal, TPR can issue contribution notices and financial support directions.

TPR used to have the power to issue contribution notices[4] as a result of being of the opinion that the “material detriment” test was met.[5] A contribution notice for breach of the material detriment test can be issued if:

- the act, or failure to act, has been materially detrimental to the likelihood of the accrued scheme benefits being received (whether the benefits are to be received as benefits under the scheme or otherwise);

- the statutory defence is not met in relation to the act, or failure to act; and

- it is reasonable to impose liability on the person to pay the sum specified in the contribution notice.

An alternative test (the “main purpose” test) allows TPR to challenge an act or failure to act designed to prevent the recovery of all or part of a debt due to the scheme under the Pensions Act 1995 s 75, or prevent such a debt from becoming due, or reduce or compromise that debt.

A section 75 debt is the money that the employer needs to pay to the pension scheme when he withdraws from it, for instance as a result of the employer’s insolvency.[6]

Contribution notices can be issued up to 6 years after an act, or failure to act, took place. Where section 75 debt notices are issued by the PPF against the insolvent company and rank as unsecured credits, with little chance of being paid, contribution notices are issued by TPR against persons who are associates of or connected with pension scheme employers. There are, therefore, greater chances of them being paid for the benefit of the scheme members.

Unfortunately, the grounds on which contribution notices could be issued were rather narrow, with the results that they failed to have and impact on corporate practice. TPR’s power to issue contribution notices for failure to comply with the material detriment test as well as financial support direction were seen as being largely ineffective. This emerged clearly in the cases of Nortel and Lehman,[7] as well as in the Bernard Matthews affair.[8]

TPR can also issue a financial support direction.[9] This is possible where the sponsoring employer is unable to support the scheme and where an associated party has been deriving financial gain from the sponsoring company (often a parent company or a company within the group structure).

In those situations, TPR can call on that party to put in place a long-term financial support plan for the scheme. TPR can issue a financial support direction if the scheme’s employer was either a service company or “insufficiently resourced”[10] at the relevant time. The procedure can start only up to 2 years after the relevant time. As a result, financial support directions have been few and far between.

Regulatory Changes Introduced by the Pension Schemes Act 2021

One of the most prominent changes introduced by the Pension Schemes Act 2021 – beyond the creation of the Collective Defined Contribution (CDC) pension scheme – has been the power to issue contribution notices if either the employer insolvency or the employer resources tests are met.[11] These two new tests intend to catch a much broader spectrum of behaviours and corporate activity than the current regime.

The “employer insolvency test” will be met if TPR is of the opinion of both of the following:

- Immediately after an event occurred, the value of a scheme’s assets is less than the value of its liabilities;

- If a section 75 debt[12] had fallen due from the employer immediately after the event, the act or failure to act would have materially reduced the amount of the debt likely to be recovered by the scheme.

Conversely, the “employer resources test” will be met if TPR is of the opinion of both of the following:

- An act or failure to act reduced the value of resources of the employer;

- The reduction was a material reduction relative to the estimated section 75 debt in the scheme if a debt had fallen due immediately before the act or failure to act occurred.

There is a statutory defence to avoid personal liability. This is if the target of the contribution notice can demonstrate that:

- They considered the potential impact of the act or failure to act on the pension scheme; and

- They reasonably considered there would be no impact; or

- They took appropriate steps to mitigate such impact.

In relation to the employer insolvency test only, there is an additional defence that the scheme’s liabilities were not less than its assets at the time of the event. While this statutory defence is problematic in its application, the expansion of TPR’s regulatory powers in case of the funder’s insolvency is welcome news.

To further support the activity of the regulator and discourage wilful or grossly reckless practices on the eve of insolvency, the Pension Schemes Act 2021 introduced two new criminal offences for the improper running of DB schemes: (a) avoidance of an employer debt; and (b) conduct risking accrued scheme benefits.[13] The offences do not just apply to company directors, as they could extend to shareholders, lenders, trustees and their advisers. Furthermore, these offences apply whether or not the perpetrators are aware of the consequences of their actions at the time.

The offence of “avoidance of an employer debt” includes any act or failure to act intended to prevent the recovery of the whole or any part of a section 75 debt. This includes preventing such a debt from becoming due, compromising its amount, or reducing the amount of a debt that would otherwise become due. The reference to a section 75 debt includes any contingent amount.

The offence of “conduct risking accrued scheme benefits” includes any act or failure to act that detrimentally affects in a material way the likelihood of accrued scheme benefits being received where the person knew or ought to have known that such a course of action would be likely to have that effect.

Particularly the latter offence is very broadly defined and wide reaching. It applies to any individual who knew or ought to have known that their conduct would have affected the pension scheme and had no reasonable excuse for their actions. As a result, there seems to be lack of co-ordination between the approach adopted by the legislator and the high threshold of “recklessness” or disregard which was all part of the earlier rhetoric in DWP’s March 2018 White Paper.[14]

Both of these offences carry the risk of a criminal penalty of an unlimited fine and/or imprisonment of up to seven years. Alternatively, the TPR could use its civil fining powers and fine a person committing one of these offences up to £1 million.

Consequences for Insolvency Practice

The Pension Schemes Act 2021 expands TPR’s powers to impose contribution notices on companies or directors, requiring them to make one-off and substantial contributions to pension schemes. These powers increase the chances to recover money from failed employers and third parties beyond the preferential status granted to the pension contributions in the last 4 months before the company’s collapse. However, they also present a significant obstacle for effective rescue procedures.

However, there are some issues, which arise from the implementation of these reforms.

The new tests have been incorporated into the Pensions Act 2004 in such a way that the six-year look-back period is available to TPR even though the Act is not expressly retrospective. Also, with reference to the “employer insolvency test”, this is triggered if the value of the scheme’s assets is less than the value of its liabilities as of the date that the employer became insolvent.[15] It is not clear, however, how this balance-sheet imbalance should be calculated, as courts have only provided occasional guidance on the notion of “assets”.[16]

While it is unlikely that courts will hold accountable directors for normal business activity, the same directors may nevertheless feel uncomfortable in taking swift and radical decisions to turn around their companies on the eve of insolvency absent any professional advice from independent experts. When time is of the essence, as in corporate restructurings and in a very complex geo-political climate caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, this may result in increased business failure rates.

With regards to new offences, they could capture a variety of players, including insolvency practitioners and other professional advisors – such as trustees and company doctors[17] – commonly involved in a restructuring. Their only defence against personal liability and an order to contribute would be to demonstrate that they acted with “reasonable excuse”, a term not defined in the legislation.

The major issue, however, is represented by the potential risk of a civil claim and fines of up to £1 million. This may well be a risk that insolvency practitioners and company doctors are not willing to accept when seeking to restructure a company that has a DB pension scheme. It may also push lenders to reject calls for additional corporate funding during restructuring. This is because their requests for additional security to support high-risk lending facilities during turnaround efforts may later be challenged as “conduct risking accrued benefits”.

Finally, the Pension Schemes Act 2021 should not be considered in isolation. Less than a year before its introduction, the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 (CIGA 2020) also introduced significant changes to the corporate insolvency framework.

One of the most notable changes in the CIGA 2020 is the introduction of a new free-standing moratorium. This causes the directors to remain in control of the company under the supervision of a monitor (a licensed insolvency practitioner) whilst they seek to rescue the company. The moratorium is granted for an initial period of 20 days, but further extensions for a period of up to 1 year are possible. The CIGA 2020 provides that notice should be given to both the trustees of the pension schemes as well as the PPF. Both the trustees and the PPF (for PPF-eligible schemes only)[18] will be asked to consent to those extensions.

The moratorium provides for a stay on any debts due at the date of the moratorium commencing. While the moratorium does not cover contributions to pension schemes arising during the moratorium (at least with reference to employees’ contributions), it covers pre-moratorium debt. The guidance from the Insolvency Service on the CIGA 2020 suggests that liabilities such as contribution notices and financial support directions under the Pensions Act 2004 should be considered to be pre-moratorium debts with a payment holiday. As a result, they will not be paid during the moratorium. Such choice reduces the cash flow to pension schemes for companies in moratorium.

Finally, a moratorium is not a “qualifying insolvency event” for the purposes of triggering a section 75 debt or the start of a PPF assessment period. For this reason, the trustees and PPF will not be able to enforce any contingent asset during the moratorium. Additionally, debt incurred by the company during the moratorium will take "super priority" status as an expense of the procedure should the company fail in its negotiations with the creditors and file for liquidation. This would certainly leave less money for other creditors - including the pension schemes - than in the case the company filed for another formal insolvency procedure from the beginning.

Another notable change is the introduction of “part 26A restructuring plans”, mutated from the schemes of arrangement.[19] A key element of the new part 26A plan is the ability to cram-down dissenting creditors. This is only possible if the dissenting creditors are no worse off in the plan than they would be in the “relevant alternative”. Additionally, one of more creditors who have an economic interest in the relevant alternative should have approved the plan. As a result, the plan may well be approved in face of the trustee’s or PPF’s opposition. At the same time, the plan should result in the survival of the sponsoring employer as a going concern, which should be a positive outcome for the pension scheme.

The CIGA 2020 should have the effect of facilitating employers to remain in business if their companies or businesses are viable. The members of any DB scheme are likely to benefit from the survival of the sponsoring employer in the long-term. At the same time, the trustees’ or PPF’s position as unsecured creditors means that their negotiating position is weaker in comparison with other key creditors. If, however, the position of the sponsoring employer deteriorates further during the moratorium or plan, it is likely that TPR may consider contribution notices against the company’s directors. Such notices, however, are unlikely to be successful, as decisions in these procedures are generally taken under the supervision of a court or insolvency practitioner, and with the consent of the majority of creditors.

Conclusion

One of the key challenges in the UK has been the inability to do deals with the DB pension scheme trustees to reduce or manage the pension liabilities so as to avoid an insolvency process.

TPR’s new regulatory powers are likely to push employers to seek more frequently clearance for future transactions. The ensuing greater trustee involvement may not necessarily protect workers. Opportunities to turn around businesses might be missed, with the results that jobs could be lost.

The same “side-effects” could be observed with the introduction of new criminal offences and related high civil fines. Finally, the purposes of the Pension Schemes Act 2021 - enhance TPR’s powers and ensure greater protection for pension schemes – sit at odd with the goals advocated by the CIGA 2020 – promote the rescue of distressed and viable businesses and enforce fair and reasonable plans on dissenting creditors –.

To conclude, it is hard to overlook the apparent conflicting and unprincipled approach followed by the legislator in reforming this area of law. Conflicting guidelines are likely to give rise to implementation and co-ordination problems for directors, insolvency practitioners, trustees, and regulators.

[1] Department for Work and Pensions, Pension Schemes Bill 2020 Impact Assessment: Summary of Impacts (January 2020) https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/lbill/58-01/004/5801004-IA-Summary-of-Impacts.pdf para 6.

[2] “PwC Pension Funding Index – new funding approach could leave DB pension schemes £70bn in the black, analysis shows” (2 February 2021) https://www.pwc.co.uk/press-room/press-releases/pwc-pension-funding-index-new-funding-approach-could-leave-db-pension-schemes-70bn-in-the-black-analysis-shows.html.

[3] See, eg, https://www.ppf.co.uk/.

[4] Pensions Act 2004, s 38.

[5] Pensions Act 2004, s 90.

[6] On the impact of section 75 debts in administrations, see: BESTrustees Plc v Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander (in administration) [2013] EWHC 2407 (Ch).

[7] Re Nortel and Lehman Brothers [2013] UKSC 52.

[8] For a detailed analysis, see M Thomas, “Bernard Matthews Limited – the Pensions Regulator’s investigation following the company’s insolvency” C.S.R. (2020) 44(5) 65; M Brown, “Bernard Matthews pension scheme: regulatory intervention report” PLC Mag. (2020) 31(8) 75.

[9] Pensions Act 2004, ss 43-50.

[10] ‘Insufficiently resourced’ means that an employer’s resources are valued at less than 50% of its estimated section 75 debt to the scheme at the relevant time. There also needs to be one or more associated or connected entities that have enough value to make up the difference. See here: https://www.thepensionsregulator.gov.uk/en/about-us/how-we-regulate-and-enforce/anti-avoidance-powers#8d28d91ec6d14ad59e99473428b1ced5.

[11] Pension Schemes Act 2021, s 103, which added to the Pensions Act 2004, ss 38C-F.

[12] Under Pensions Act 1995, s 75 as subsequently amended, participating employers become liable for what is known as a “section 75 employer debt” when they withdraw from the Scheme. This debt is calculated on a ‘buy-out’ basis, which tests whether there would be sufficient assets in the Scheme to secure all the member benefits by buying annuity contracts from an insurance company.

[13] Pension Schemes Act 2021, s 107, which added to the Pensions Act 2004 ss 58A-D.

[14] Department for Work and Pensions, Protecting Defined Benefit Pension Schemes (Cm 9591, March 2018) at 10.

[15] BESTrustees Plc v Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander Ltd (In Administration) [2012] EWHC 629 (Ch).

[16] Re Storm Funding Ltd (in administration) [2013] EWHC 4019 (Ch).

[17] V Finch, “Corporate rescue processes: the search for quality and the capacity to resolve” J.B.L. (2010) 6 502 (listing company doctors as specialists in turnaround practices).

[18] The Pension Protection Fund (Moratorium and Arrangements and Reconstructions for Companies in Financial Difficulty) Regulations 2020 made under the CIGA 2020 (7 July 2020) allow the PPF to exercise the voting rights of the trustees in relation to both a moratorium and a part 26A restructuring plan.

[19] Companies Act 2006 part 26.

1st Review of the Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016 – What’s Next?

written by Dr. Eugenio Vaccari (Lecturer, RHUL)

Published on 24 March 2021

The UK government has launched a consultation seeking stakeholders’ views on the insolvency rules that set out the detailed requirements for company and individual insolvency procedures in England and Wales to improve their effectiveness. This blog post outlines the purpose of the consultation, and it sheds some lights on some of the challenges of the current system of rules.

The Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016

The Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016 (“the Rules”) came into force on 6 April 2017. The Rules set out the detailed procedure for the conduct of company and individual insolvency proceedings under the Insolvency Act 1986, providing the framework giving effect to the regime specified in the Act. They represent the single most significant piece of legislation in respect of the insolvency regime operating in England and Wales, after the Insolvency Act itself; and the largest, with 900+ rules in the main body and numerous additional schedules covering specific topics.

The Rules in their current form represent the consolidation and modernisation of the earlier Insolvency Rules 1986 and the accompanying legislation that had developed in the intervening thirty-year period. The latest iteration of the Rules has been enacted to support changes to the insolvency regime that had been made in the Deregulation Act 2015 and the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 (“SBEEA 2015”), as well as to implement several brand-new policies that aimed to modernise the regime.

The Rules include a requirement, introduced by the SBEEA 2015, to carry out a review of the secondary legislation and publish a report setting out the conclusions of that review. The report must be published within five years of 6 April 2017, the date that the Rules came into force. As part of that review, the Insolvency Service has, therefore, issued a call for evidence in order to gather information regarding the operation of the Rules in the three years since their introduction.

The consultation is now taking place, and stakeholders – including insolvency practitioners, the legal profession, directors, creditors and business and consumer groups – have until the 30th of June at 11:59 pm to submit their views.

The Call for Evidence

This call for evidence is to request information regarding the impact that the Rules have had and the way that they have worked since coming into force, with particular focus on whether they succeeded in achieving their objectives.

The primary aim of the Rules is to establish the detailed procedure for the conduct of company and individual insolvency proceedings under the Insolvency Act 1986, giving effect to that Act. That objective was shared with the previous Insolvency Rules 1986 (SI 1986/1925). The Insolvency Service is particularly interested in identifying gaps in the Rules, which may affect the operation of the regulatory framework.

Initial representations from insolvency professionals making direct use of the legislation suggest that for the most part the Rules are operating as intended, but that there remain a number of areas where further changes and clarifications are sought.

One of the primary concerns is whether the Rules are user-friendly and devoid of ambiguity. The Insolvency Service is seeking views on this point from “traditional” users. However, the extent to which these Rules are clear and unambiguous should not simply be a question for experienced, traditional users. Such question should preferably be asked to a larger audience, including legal professionals and accountants not directly involved with insolvency matters.

Another concern is to assess how the Rules have operated with reference to small businesses. Unlike other common law countries such as the U.S.,[1] it seems that England is not willing to opt to reform its insolvency regulatory framework by introducing separate rules and procedures applicable only to small businesses.

Overall, the questions focus on enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of the Rules and, as a consequence, of the English insolvency framework.

Challenges

A number of issues have been highlighted for reform. Some of these issues include the Rules’ abolition of prescribed forms, the new creditor opt-out from communications, and the use of electronic communications and filing of documents.

At the same time, the Rules have introduced most welcome changes for the management of insolvency procedures. For instance, part 15 of the Rule consolidates the instructions on notices, voting rights, exclusions and appeals. It introduces consistency between the different insolvency and restructuring procedures. Some changes, such as the abolition of physical meetings and the introduction of new decision-making procedures (including deemed consent) are radical in nature.

Arguably, this is the most controversial reform introduced by the 2016 Rules, for which there was very little support during the consultation process. Supporters argue the new Rules reflect the reality of limited creditor engagement and will save both time and money whilst allowing technology to play its part in the decision-making process. Critics argue the abolition of physical meetings will only deter creditor engagement still further as well as depriving creditors of the opportunity to question directors and debtors and compare notes with one another. Yet, such change seems to have worked well in practice, especially in light of the additional issues caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

It is quite common to dismiss the importance of consultations on rules as procedures. The focus is mainly on the law and its provisions. However, how the law is applied is a central part of any regulatory framework. A good law applied in an inefficient manner may hinder the functioning and attractiveness of a procedure and/or regulatory framework.

It is likely that stakeholders will advocate for further changes, designed to reduce red tape challenges and facilitate the practitioners’ duties and responsibilities in small procedures, where few or no assets are available for distribution. We will update this blog post once the consultation is closed and the Insolvency Service has issued a final report with the key takeaways from the consultation.

[1] Effective February 19, 2020, Congress enacted new bankruptcy legislation granting debtors the option to elect a new subchapter V of Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code – see Small Business Reorganization Act of 2019, Pub. L. No. 11654, 133 Stat. 1079.

Pre-packaged Administrations in the UK: A Preliminary Assessment of the Recent Reforms

written by Dr. Eugenio Vaccari (Lecturer, RHUL)

Published on 15 June 2021

As I mentioned in a previous blog post published on this website,[1] the English corporate insolvency framework has gone through significant changes in recent times. The Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 (CIGA 2020), which completed its progress in the Parliament and received Royal Assent on 25 June 2020, introduced a series of temporary measures and long-term reforms, thus effecting a significant change to the English corporate insolvency framework.

One of the areas, which was not directly affected by the reforms is administration. The administration procedure was introduced by the Insolvency Act 1986 (IA 1986), as amended by the Enterprise Act 2002 (EA 2002). Administration provides a company, limited liability partnership or partnership with a breathing space to allow a rescue package or more advantageous realisation of assets to be put in place. The EA 2002 introduced Schedule B1 to the IA 1986 to make the administration procedure quicker, cheaper and less bureaucratic than before.

Administration should be used to achieve one of the following purposes: rescuing the company as a going concern, achieving a better result than liquidation or, in the last instance, realising the company’s assets to make a distribution.[2] Nevertheless, companies and practitioners find the traditional administration procedure too cumbersome, expensive and lengthy to achieve such results. As a consequence, they devised revised approaches, such as light-touch and pre-packaged administration procedures, to promote the rescue of distressed yet viable companies.

Light-touch administrations differ from traditional administration procedure as the existing management is not displaced by the appointed insolvency practitioner to run the company. In other words, the administrators effectively give this consent to the board to exercise certain powers within agreed parameters.

In pre-packaged administrations (pre-packs), the existing management – frequently under professional advice from an insolvency practitioner – agree on selling the business to a third party before the commencement of the administration procedure.[3] As the sale is effected shortly after the commencement of the procedure, the creditors have no time to vote on the plan before the business and valuable assets are disposed of.

This blog post focuses on pre-packs. As I mentioned in a recent article,[4] pre-packs give rise to concerns of "phoenixism", as the company which buys the debtor’s assets usually continues to operate in the same sector, premises and with a similar name as the now defunct debtor. They also give rise to concerns of collusion, because the debtor is sold to a party, often connected with the lender, for a fraction of the company’s liabilities on the basis of negotiations occurred behind closed doors. It has also been remarked that pre-pack businesses are not marketed in a competitive manner, which may lead to undervalue sales that are short-term fixes to write off liabilities, thus failing to ensure the long-term viability of the company.

There have already been several attempts at reform, including the Graham Review into Pre-pack Administration in 2014[5] which introduced several recommendations including the Pre-Pack Pool, and a revised Statement of Insolvency Practice 16 (SIP 16), introduced in 2015.[6] In the meantime, cases such as Re Moss Groundworks Ltd[7] showed that SIP 16 was still not being fully complied with, and that pre-packs continued to be inherently problematic. Back in June 2020, Parliament granted to the Government an extension to end of June 2021 to the power to legislate on pre-packaged sales to connected persons. This legislative power was originally granted by the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 (SBEEA 2015) but later expired in May 2020.[8]

On 8 October 2020, the UK Government published draft regulations[9] aimed at pre-packaged sales to connected parties which occur by means of an administration proceeding. Such proposal was later approved by Parliament with modifications and resulted in The Administration (Restrictions on Disposal etc. to Connected Persons) Regulations 2021 (SI 427/2021) (Administration Regulations 2021).[10]

The Administration Regulations 2021 came into force on 30 April 2021 and apply to administration procedures commenced on or after 1 May 2021. It also triggers changes to the SIPs. The SIPs were revised following a public consultation by the Joint Insolvency Committee (JIC) with changes affecting SIP 16 (Pre-packaged sales in administrations); SIP 13 (Disposal of assets to connected parties in an insolvency process); and the withdrawal of SIP 4 (Disqualification of directors).

The Administration Regulations 2021

In order to reduce the risks of collusion and undervalued sales in pre-packs without unduly affecting – at least in the Legislator’s intent – the speed and efficacy of the procedure, new requirements were put in place to effect pre-packs to connected parties.[11] Under regulation 3, “substantial disposals” by means of one or more transactions of all or a substantial part of the debtor’s business or assets is prohibited in the first 8 weeks from the commencement of the administration unless either of the following conditions are met:

- The company’s creditors have approved such disposal;

- The administrator has obtained a qualifying report for such disposal.

These requirements are in addition to (and do not replace) existing statutory and regulatory requirements, which apply to administrators.

If the creditors’ approval is sought, the administrator needs to send them a proposal, and the sale needs to be effected in accordance with the creditors’ approval. In practice, it seems unlikely that administrators would choose this approach given the time it can take for consent to be achieved, and the risks associated with the hold-out attitude of some (categories of) creditors.

As for the qualifying report, this has to be commissioned to an independent evaluator by the connected party, who is seeking to buy the debtor’s business or assets. The administrator needs to be satisfied that the individual making that report had sufficient relevant knowledge and experience to make a qualifying report.[12] The report needs to include a statement that the evaluator is satisfied that the consideration to be provided for the relevant property and the grounds for the substantial disposal are reasonable in the circumstances.[13] The report also needs to include the evidence used by the evaluator to reach such conclusion, and the reasons for their advice. The report needs to be shared with the registrar of companies, as well as every creditor of the company.

A negative qualifying report (stating that the grounds for disposal or the consideration are not reasonable) does not prevent the administrator from completing the disposal, However, should the administrator proceed in that way, they must make a statement setting out their reasons for doing so when the evaluator was not satisfied it was reasonable. If the administrator simply states that the disposal is justified without any explanation and reference to the evaluator’s report, then it may be difficult for an administrator to show that they have complied with the requirement to consider the contents of the report.

One of the most striking innovations of the Administration Regulations 2021 is that the evaluator – a role in the past covered sui generis by the Pre-Pack Pool – needs NOT to be an insolvency practitioner. While a long list of exclusions applies,[14] and while the Legislator set out clear criteria to determine whether the evaluator is acting in an independent manner,[15] under the Administration Regulations 2021 the evaluator needs only to have sufficient relevant knowledge and experience,[16] and be covered by professional indemnity insurance against liabilities to the administrator, the connected person, and creditors.[17]

Preliminary Comments

It is expected that the most common route to have the pre-pack deal approved and effected will be through the qualifying report of the independent evaluator. As a result, the success of the Administration Regulations 2021 seems to rely on the integrity of the evaluators.

In this context, significant questions are raised by the choice not to rely on insolvency practitioners or the existing Pre-Pack Pool for the role of the evaluator. The Pre-Pack Pool was an independent body and a limited liability company constituting of experienced business people, who are selected following a public recruitment exercise. Its members used to offer an opinion on the purchase of a business and/or its assets by connected parties to a company where a pre-packaged sale is proposed. In other words, the Pre-Pack Pool was doing what evaluators are now asked to do under the newly enacted Administration Regulations 2021.

The Legislator is certainly right in considering that the knowledge and experience needed to make such assessment is not a prerogative of insolvency practitioners. It is also likely that, by expanding the range of people, who could provide such report, costs of such reports are likely to be reduced and the report is likely to be provided in a timely manner.

At the same time, the requirement for insurance might restrict the market to those professionals, who already practice in the field and are regulated by independent bodies. The Insolvency Service, in its guidance on the Administration Regulations 2021, openly admits that certain professions (surveyors, accountants, lawyers with a corporate background and insolvency practitioners) are more likely to have the relevant knowledge and skills required to act as an evaluator.[18]

As these insurances are likely to be expensive, a professional market for evaluators may develop, but such qualifying reports are unlikely to end up being affordable for small and micro-enterprises. Finally, the detailed requirements in terms of the content of such reports may push larger corporate debtors to opt for alternative rescue mechanisms, such as the revised Pt 26A restructuring plans[19] - which, moreover, offers some degree of protection in case one class of impaired creditors decides not to support the restructuring plan -.

In any case, the new Administration Regulations 2021 represent a sea change (from a procedural standpoint) in the way pre-packs can be conducted in this country. They have the potential of further restricting access to a quick and inexpensive way to rescue a company, at a time where small and micro-enterprises are suffering the most and international institutions are calling for tailored mechanisms to promote their rescue and survival rates.[20] It is, therefore, surprising and disappointing to read in the Explanatory Notes to the Administration Regulations 2021 that ‘an impact assessment has not been produced for this instrument as no, or no significant, impact on the private, voluntary or public sector is foreseen’.

In practice, insolvency practitioners have been conducting pre-packaged sales in accordance with the SIP 16 guidelines for a long period of time. The majority of them have developed well-honed internal procedures to ensure that sales to connected parties are justified. The use of evaluators will doubtless increase costs, result in some delay, and push more small and micro-enterprise to liquidate rather than rescue their business.

While some retailers and suppliers welcome the introduction of these new rules,[21] it is submitted that the new Administration Regulations 2021 result in additional hurdles for all the parties involved in a pre-pack, without remarkably reducing the risks of strategic or abusive use of the procedure. As a result, there are reasonable grounds to question the desirability and content of such rules.

[1] E Vaccari, ‘Pre-packaged Administrations in the UK: Nothing New under the Sun?’ (2 February 2021) <https://www.royalholloway.ac.uk/research-and-teaching/departments-and-schools/law-and-criminology/research/blogs/>.

[2] Paragraph 3, Schedule B1 IA 1986.

[3] Statement of Insolvency Practice 16: the term ‘pre-packaged sale’ refers to an arrangement under which the sale of all or part of a company’s business or assets is negotiated with a purchaser prior to the appointment of an administrator and the administrator effects the sale immediately on, or shortly after, appointment.

[4] E Vaccari, ‘English pre-packaged corporate rescue procedures: is there a case for propping industry self-regulation and industry-led measures such as the Pre-Pack Pool?’ (2020) 31(3) I.C.C.L.R. 170, 177.

[6] <https://insolvency-practitioners.org.uk/uploads/documents/f30389ce35ed923c06b2879fecdb616a.pdf>.

[7] [2019] EWHC 2825 (Ch).

[8] Section 8 of CIGA 2020.

[9] Draft Administration (Restrictions on Disposal etc. to Connected Persons) Regulations 2020 <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pre-pack-sales-in-administration>.

[10] While the Administration Regulations 2021 are NOT restricted to pre-packs, such substantial disposals to connected parties usually take place in the form of pre-packs.

[11] “Connected person” is defined in paragraph 60(A)(3)-(5) of Schedule B1 IA 1986. These are relevant persons in relation to the distressed debtor, or companies connected to the debtor. Relevant persons are a director or other officer, or shadow director, of the company; a non-employee associate of such a person; and a non-employee associate of the company. A company is connected with another if any relevant person of one is or has been a relevant person of the other.

[12] Regulation 6(2), Administration Regulations 2021.

[13] Regulation 7(h)(i), Administration Regulations 2021.

[14] Regulation 13, Administration Regulations 2021.

[15] Regulation 12, Administration Regulations 2021.

[16] Regulation 10, Administration Regulations 2021.

[17] Regulation 11, Administration Regulations 2021.

[18] The Insolvency Service, ‘Guidance about the requirement for independent scrutiny of disposals of company assets in an administration’ (30 April 2021) <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/requirements-for-independent-scrutiny-of-the-disposal-of-assets-in-administration-including-pre-pack-sales/requirements-for-independent-scrutiny-of-the-disposal-of-assets-in-administration-including-pre-pack-sales> at [7].

[19] Sections 901A-901L, Companies Act 2006.

[20] https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance. See also OECD, ‘Statistical Insights: Small, Medium and Vulnerable’ (2020) <https://www.oecd.org/sdd/business-stats/statistical-insights-small-medium-and-vulnerable.htm>

Local Public Entities in Distress – An English Perspective

written by Dr. Eugenio Vaccari (RHUL) and Prof. Yseult Marique (University of Essex (UK), FöV Speyer (DE), UC Louvain (BE))

Published on 16 November 2022.

This post was first published as an Inside Story by INSOL Europe.

Introduction

This is arguably one of the most difficult times in history for local authorities around the world. Authorities in developed countries like the UK make no exception.

Councils in the UK face issues that are common to all types of local entities, such as inflationary costs for the provision of essential services (particularly social care) and reduced transfers and tax collection abilities due to the current global economic recession. In addition, they face unique challenges. These include increasing costs to service the commercial debt they had been encouraged to take in previous years, a dwindling and aging population, and increased demands of essential services from a more vulnerable population.

Building on a study funded by INSOL International and recently published in the INSOL International Technical Library, we discuss the treatment of financially distressed English authorities. The purpose of this short article is to uncover the causes of municipal failures, assess the remedies available under the law and discuss whether regulatory changes are needed to improve the status quo.

Why Do Councils Fail?

The short answer is: for a lot of reasons, and quite frequently for more than one reason. However, the recent experience of financially distressed local entities suggests that at least three triggering factors are recurring.

The first one is malpractice, and it is exemplified by the case of Liverpool. In November 2022, Rt Hon Michael Gove, Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities and Minister for Intergovernmental Relations, appointed a financial commissioner at Liverpool to oversee the council’s dire financial situation. This appointment follows a second critical commissioners' report. These commissioners were appointed in 2021 after an emergency inspection found a “serious breakdown of governance” and multiple failures to provide best value to taxpayers in the city. The inspection was triggered by the arrest of the city mayor and other top civil officers (December 2020) as part of a police investigation into allegations of fraud, bribery, corruption and misconduct in public office. Unfortunately, it does not seem that the changes introduced since 2021 have resulted in a marked improvement of the financial situation of the council. In October 2021, shortly after appointment, the commissioners reported that Liverpool faced a £33m shortfall for the 2022-23 budget. By the time of the second report in June 2022, this figure had increased to £98.5m to 2025-26, thus justifying the urgent appointment of a financial commissioner.

The second “triggering factor” is poor governance. Poor governance and accountability are common elements in almost all the recent cases of distressed councils in the UK. However, they were probably the determining factors for some of the best-known municipal fallouts in recent times, such as Croydon and Nottingham.

The London Borough of Croydon – whose case was analysed in detail in a report from the Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee – issued a section 114 notice (more on this in the next section) in 2020-21 after it emerged the authority was unable to balance its budget, effectively declaring itself bankrupt. A public interest report from the council’s external auditors (October 2020) highlighted that the council reported significant overspend in areas such as children’s and adult social care. However, the same report questioned the use of the flexibility granted by the government to deal with these issues. Finally, the report argued that the main factor for the council’s financial demise was its excessive corporate borrowing, which led the council to invest in under-performing companies and exposed future generations of taxpayers to significant financial risk. As a result of its financial difficulties, following a complete overhaul of its corporate structure, Croydon has received two capitalisation directions of £75m in 2020-21 and £50m in 2021-22 allowing the use of capital resources for revenue spending to cover budget deficits. Despite this, Croydon has received minded approval for a third direction in 2022-23 worth £25m.

The case of Nottingham is somehow similar to Croydon. The issues in the city became of public knowledge after the council’s external auditors issued a public interest report (August 2020). The report raised concerns on how a wholly-owned subsidiary of the council, Robin Hood Energy, was being run, and the lack of financial information shared with the external auditors and the council itself. This report was followed by the government’s appointment of an improvement and assurance panel (November 2020) and finally by the council being forced to issue a section 114 notice in December 2021 after it emerged that the authority unlawfully used funding earmarked for its housing on revenue spending.

Finally, the third triggering factor is failure in commercial investments. Several councils are struggling financially to either refinance or service their commercial debt, especially at a time of rising interest rates. Some of them, such as Slough and Thurrock, failed in their efforts to avert external intervention and “bankruptcy”.

The case of Slough hit the news in July 2021, when its CFO issued a section 114 notice after some failed attempts to recapitalise the borough with funds from the government and financial investors. This procedure has led to the sale of most of its properties and assets at a loss – some of them bought just a few years before in an attempt to diversify and increase the revenue capacity generation of the authority.

This case shares some similarities with the demise of Thurrock. In May 2020, a major investigation from the Financial Times unveiled that Thurrock, a local authority in Essex, borrowed almost £1bn from 150 other UK local authorities and pension schemes to fund its renewable energy assets. However, the case did not result in governmental actions until recently, partly due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Only in September 2022, the government exercised its powers under section 15(11) of the Local Government Act 1999 to nominate Essex County Council as a commissioner for Thurrock, due to the scale of the financial and commercial risks potentially facing the authority and the lack of proper, timely and radical intervention from the council. This intervention was shortly after followed by an authorisation to borrow almost £840m from the Public Works Loan Board (PWLB) – a body attached to the Treasury that funds councils’ infrastructure spending – to refinance some of the loans taken from other UK local authorities.

Slough and Thurrock are not isolated cases. Local authorities such as Spelthorne in Surrey have borrowed heavily from the PWLB to offset the cuts in direct transfers from the central government. The issue is that if and when these investments fail – a circumstance that is rendered more likely by the lack of commercial and financial expertise in the councillors running these entities – local and national taxpayers are left to deal with the huge financial consequences of these failed entrepreneurial activities.

What Are the Remedies Available to Financially Distressed Councils?

The general approach followed by English law is to provide a series of mechanisms to local authorities to deal with financial difficulties before they become insolvent. These preventive restructuring measures include reducing costs, sharing services with other local authorities, and mergers between local authorities. It is also possible for councils to rely on loans from PWLB, bonds, and loans, as well as raising local taxes.[1]

Should these measures fail, the framework for dealing with councils in financial distress is outlined by the Local Government Finance Act 1988 and the Local Government Act 1999. The key figures are the CFO of the local authority and the Secretary of State.

Uniquely across the public sector, CFOs have the power and legal responsibility to suspend a local authority’s spending for a period of time if they consider the council not to have a balanced budget or if there is an imminent prospect of default. In serious cases of financial distress, CFOs have a more general power to stop a local authority from entering into new transactions and performing some of the existing ones. This power is granted by section 114(3) of the Local Government Finance Act 1988 (“section 114 notice”).

CFOs will only issue such a notice if they have formed the view that future expenses are out of control, to the point that the local authority to which they are appointed is likely to end the financial year with a budget deficit and that it is impossible to broker a solution without issuing a section 114 notice.

It is quite likely that the procedure will result in the appointment of new independent commissioners for the local authority in debt. Newly-appointed independent commissioners will deal with a local authority’s financial distress without liquidating it as, under English law, local authorities cannot be liquidated. They can only be rescued. Local authorities cannot be subject to other debt resolution mechanisms (for example, state oversight, active supervision, or financial assistance from other authorities) apart from those outlined in this section.

What Else Can Be Done?

Section 114 notices are late warning signals. The consequences of issuing such notices are severe for the councils that issue them. All but essential expenses are frozen, and councils may be forced to merge with neighbouring ones; for instance, Northamptonshire councils were forced to merger in two unitary authorities in 2018.

The harshness of the consequences associated with section 114 notices have been designed to push councils to take timely decisions to avoid experiencing serious financial pressures. Yet, the changed policy and funding environment described in this paper coupled with a lack of expert auditors to supervise a council’s activities may lead to local authorities experiencing serious financial difficulties. If this happens, the consequences for councils, their workers, the services they provide and their existing procurement contracts are draconian.

This punitive approach towards failure has no equivalent in the English corporate or personal insolvency law framework, and it lacks proper theoretical justification. As mentioned in our paper submitted to INSOL International, reforms aimed at supporting local authorities experiencing financial difficulties, rather than punishing them for being indebted, are needed to realign the treatment of local public entities in distress with the rest of the English insolvency framework.

The UK’s legislative framework for dealing with local authorities in distress is inadequate. No day passes without news that other councils are likely to issue a section 114 notice – see, for instance, the recent warning about the Tory-run councils of Kent and Hampshire. These procedures have lasting impacts on local taxpayers and, especially, on vulnerable citizens. We believe that the time is ripe to discuss the implementation of a more mature, comprehensive framework aimed at addressing the causes of municipal failures. This framework should result in the implementation of an alert, modular system designed to take prudent fiscal measures at the first signs of crisis, without necessarily resulting in the displacement of the council’s existing management.

Please contact us and Prof Laura Coordes (laura.coordes@asu.edu), follow us on Twitter and do check our webpage for more news on our studies on local public entities in distress, or if you are interested in contributing to our research.

[1] For a clear outline of the preventive restructuring solutions, see N Gavin-Brown, “Restructuring Options for UK Local Authorities” (20 August 2018) available at https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/analysis/restructuring-options-uk-local-authorities.

Human Rights Law

Roe v. Wade Ruling: Seeing the Trees, Not the Forest

written by Dr. Jenny Korkodeilou (Lecturer, RHUL)

Published on 28 June 2022

“One day you and I will have to have a little talk about this business called love. I still don’t understand what it’s all about. My guess is that it’s just a gigantic hoax, invented to keep people quiet and diverted. Everyone talks about love: the priests, the advertising posters, the literati, and the politicians, those of them who make love. And in speaking of love and offering it as a panacea for every tragedy, they would and betray and kill both body and soul.”

Oriana Fallaci, Letter to a Child Never Born (1975)

Fallaci’s writing is disturbingly honest and yet poetic. She talks about personal (political), inconvenient truths in an intimate and humane manner. Let’s be specific: Oriana Fallaci wrote a book centred on the dialogue (monologue) a young professional woman has with the foetus she is carrying in her uterus via a letter. In her book, Fallaci beautifully navigates things that mothers-to-be often think but seldom dare to share and discuss even with people they trust the most. She goes through the ambiguities, dilemmas, anxieties that motherhood entails and regards motherhood as a responsible moral choice rather than as a merely social mandate.

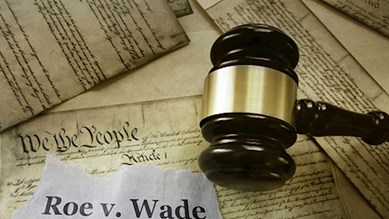

I am in a perpetual quest for good words, and ‘choice’ is a well-chosen word here for it captures the core notion of the (anti-) abortion rights’ debate that’s been going on (and off) for many decades now. In June 2022 the historic and for many very controversial US Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade was overturned: in 1973 the US Supreme Court ruled that state prohibitions (see Texas) on abortions during the early months of pregnancy were unconstitutional, therefore establishing the right of women to have an abortion or not. I am not going to dive into the constitutional meaning, implications and limitations of Roe’s ruling. It is evident though that there are two sides: the pro-rights’ movement with fervent (feminist) voices advocating for women’s bodily and reproductive autonomy and the pro-life camp maintaining that abortion is about killing another human being, even if this is not born yet.