By Dr James France, on behalf of the Greenhouse Gas Research Group.

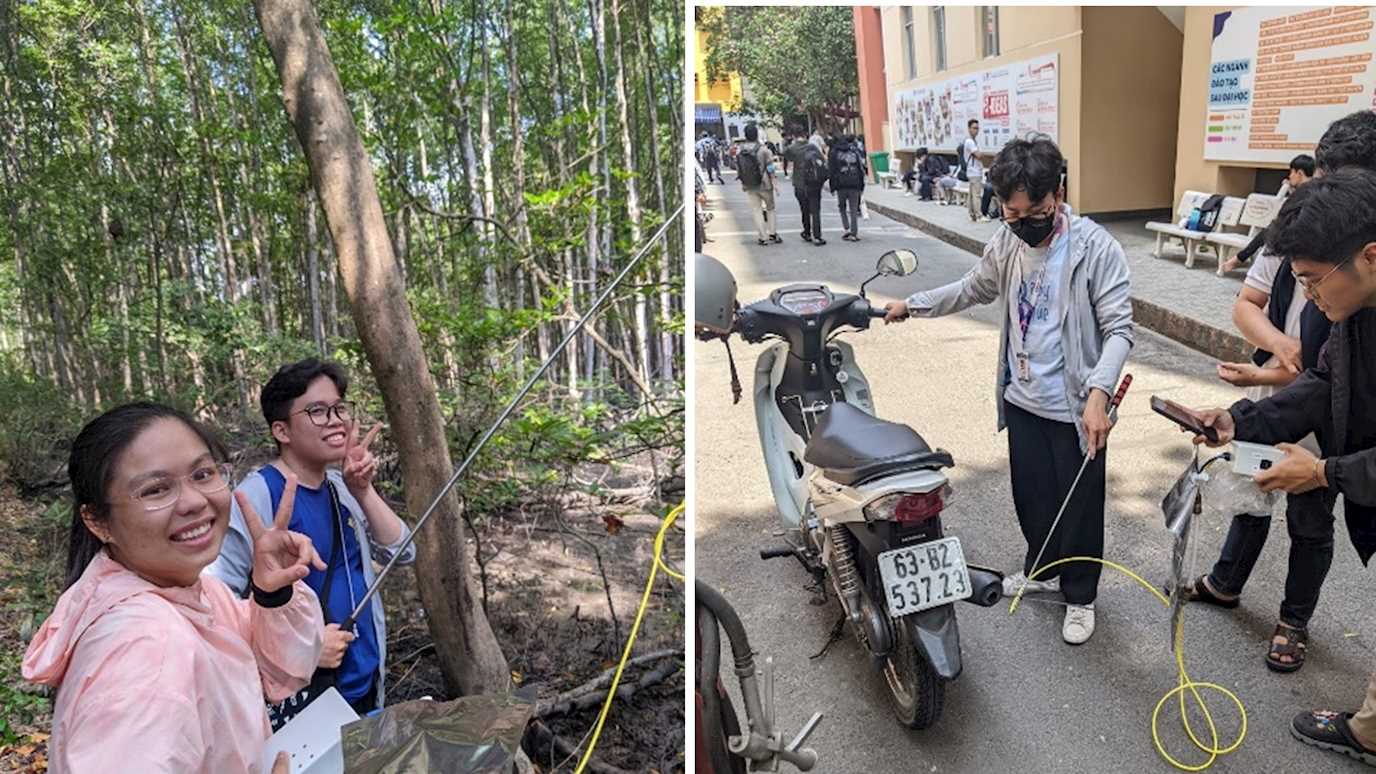

Students from VNU learning to take air sample for methane analysis.

The concentration of methane in the atmosphere is currently rising at a rate of around 15 parts per billion (ppb) per year ( https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends_ch4 ). Whilst that might not seem to be particularly significant at first, the increase of methane in our atmosphere from a pre-industrial concentration of around 700 ppb to today’s values of nearly 2000 ppb is responsible for more than 25% of the global warming we are experiencing currently. However, the lifetime of a methane molecule in the atmosphere is only around 9 years, so reducing methane emissions can have a very rapid effect on mitigating climate change.

The main sources of methane are well known and can be broadly split into anthropogenic sources (~60%); energy, waste and agriculture, and natural sources (~40%); wetlands, geological seeps, and water bodies. But within these categories, subtle trends can be difficult to track and accurately quantifying methane emissions at scales smaller than large regions can be surprisingly challenging. There is much good work occurring with the development of satellites designed to measure and quantify methane such as TROPOMI and the soon to be launched MethaneSAT where the data is / will be publicly available, and there are excellent ground based networks measuring methane such as fluxnet and the NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory programme (https://fluxnet.org/ and https://gml.noaa.gov/obop ). However, there are still a lot of data gaps and large parts of the world where satellites struggle to observe due to clouds or high latitudes. Here, in the Royal Holloway Earth Sciences Greenhouse Gas Research Group, we have an ongoing programme of work around the world to measure methane emissions from a range of under-studied and poorly quantified sources of methane around the world.

There are several reasons to be studying methane emissions – the first is the most immediate and critical, finding targets for mitigation so that the total rate of emissions to the atmosphere can be reduced. The second is to understand how the changes in the natural world due to temperature increases are affecting the natural emissions of methane. It is crucial that we understand what our current emissions baseline is, so that we have benchmarks to measure progress against – without this it will be very difficult to evaluate the impact of mitigation measures put in place.

Some snapshots of our recent work:

Sources of methane in the urban environment: Ho Chi Minh City (with Vietnam National University and University of East Anglia).

Many western nations have their urban methane emissions dominated by leaks from the natural gas distribution grid. In nations such as Vietnam where a gas grid does not exist and propane is mainly used for cooking, the sources of methane are very different. Here, we encountered emissions from the sewage systems, local wetlands, vehicles, and very large emissions from the city landfill. More work is now ongoing trying to establish the impact of these emissions on the urban atmosphere and work with Harvard to see if any of the satellites can quantify the large emissions from the landfills.

Very large methane emissions from tropical wetlands (with the British Antarctic Survey)

The large tropical wetlands are a difficult part of the world to study, cloud cover prevents satellites giving clear pictures with any regularity and the scale of the wetlands are often so vast that ground-based instrumentation cannot capture the full influence of the region easily. Wetlands may be incredibly important in understanding the trends in methane in recent years, with estimations suggesting that wetlands account for ∼30% of the total CH4 flux to the atmosphere, but those wetlands with the greatest emissions (in the tropics) are the least well studied. The methane is produced by microbes living in the anaerobic conditions in the flooded soils, which is then transported through plants or by diffusion through the water column – all dependent on rainfall and temperature, with the expectation that as the tropics warm and become wetter, methane emissions from this natural source will become greater. This is known as a climate feedback effect.

In Bolivia, we used a twin-otter aircraft as a platform to measure the amount of methane in the atmosphere by drawing in the air through an inlet on the side of plane and continuously measuring with a high precision instrument. From this, and some measurements of meteorology, we were able to determine how much methane was being emitted during the peak rainy season from the wetlands and it was a surprisingly large amount (https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2206345119).

Other less glamourous, but equally important work by the group involves us measuring emissions from locations across the UK, working closely with both regulators and industry developing methods so that methane emissions can be quantified correctly, and potential for mitigation identified for a range of sources including the gas distribution network, landfills, and biogas facilities. We’re hopeful that the engagement from industry suggests that there is a willingness to act on methane and whilst the best time to act would have been earlier, the next best option is to focus on mitigation now.