Learning your A, B, C’s isn’t easy – Professor Kathleen Rastle’s research into the ‘science of reading’ is transforming how reading is taught around the world, changing lives for millions

Before you read any further, just pause for a minute.

Think about what you just did.

You read that.

And you’re reading this.

What you might take as an effortless process, and one that you can’t stop yourself from doing, is actually quite an amazing thing. It’s something that as humans, we do not have a natural instinct towards doing. In fact, for many humans it’s something they’ll never learn how to do.

For decades, educators have battled over one question: What’s the best way to teach reading? Should children memorise whole words by sight? Or learn phonics, the system that links letters to sounds? These opposing camps created what became known as the “reading wars,” a battle fought in classrooms, policy papers, and teacher training programmes.

“We forget that it's a painstaking process - it takes at least 10 years to learn to read.”

For psychologist Professor Kathleen Rastle, unlocking the secrets of reading is the key to changing outcomes for millions. “It’s the foundation of so much – reading leads to knowledge, income, economic growth, health, well-being, social interaction, cultural capital – so much flows from literacy.” She has formed connections with educators and governments worldwide, seeing her work adopted into policy and put into practice in classrooms to help solve the problem of why children aren’t reading. And she’s not finished yet.

The science of reading

Reading is a relatively new cultural invention that developed alongside writing about 5000 years ago. It’s a precise skill we must learn through hours, months and years of repetitive teaching and practice. It’s a skill that must be developed and mastered before reading can turn to comprehension and we become skilled readers - able to understand and interpret what we read.

“We’re learning to link arbitrary visual symbols – lines, squiggles and dots – with spoken language.” says Kathy.

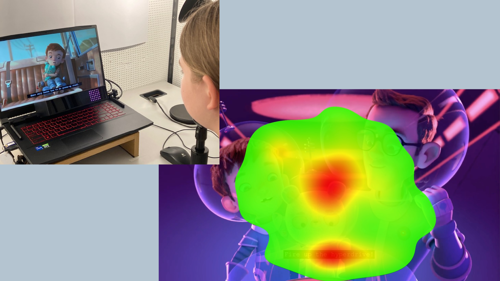

As a psychologist, Kathy has spent her career investigating the science behind reading, studying exactly what’s happening in the brain as it learns to interpret a writing system, no matter which language is being learnt. Beginning by studying how literate adults read, her investigations also led her to examine how reading is taught.

Realising she had gathered a great deal of evidence about which methods produce the best results she started to consider how her research could be used to make a difference and help children learn to read.

Ending the reading wars

Recognising that many schools around the world did not take the science into account for teaching people to read, Kathy and her collaborators set out to publish a definitive article about what works. Pulling together years of research, they published Ending the Reading Wars in 2018, little knowing the influence it would go on to have.

“We couldn’t possibly have imagined how viral that paper would go.”

Covering the whole reading journey from learning what letters are to becoming a confident reader, the paper laid out what the scientific evidence showed to be the most successful way to learn to read and offered guidance on how to use this science in teaching methods. “For the first time we were able to say, here’s what the science is, these are the implications for educational policy and teaching practices, and up until now, this science has been largely ignored by education.”

Hear Kathy discuss her research after winning the ESRC's Celebrating Impact Prize

Using phonics

It was their work on phonics that had the most impact. Phonics is a teaching method that links sounds to letters, allowing students using alphabetic languages like English to decode words. Using the research, Kathy and her collaborators demonstrated that it is the most effective way to get children reading.

|

“Phonics delivers,” Kathy says. “It’s very expensive to teach children to read, but phonics is a system teachers can master. It can be built into the curriculum, and when delivered well, it’s a system that can deliver huge returns in terms of children’s reading.” |

Governments and organisations took note and took action.

- Parliamentary enquiries from the UK to Scotland, Canada to Australia have cited the research,

- The UK and Australia have featured details from it within reading frameworks, curriculum reviews, and guidance literature,

- The state of New South Wales in Australia introduced phonics screening in primary schools, while the state of Massachusetts in the USA used the research to inform their new early years (K-3) literacy curriculum / Mass Literacy programme,

- It’s been used in curriculum plans in schools in the UK and featured in teacher blogs and articles in the UK, USA, Australia, Canada and Netherlands,

- Across the UK, the USA, Australia, and in Africa, educational leadership organisations and literacy charities are using and advocating these techniques,

- Publishers from the UK, the USA, Canada, and Australia have adopted and used the research in educational materials & reading schemes.

Back in the UK, Kathy works frequently with developers of reading schemes used in thousands of schools to ensure that their programmes are evidence-based. And UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) – the national funding agency for science and research – has chosen the project to be featured in an advertising campaign to demonstrate the positive power and impact this kind of work can offer.

Taking the fight global

But Kathy wasn’t done. If science could transform classrooms in the UK, why not everywhere else?

“As reading scientists, we have a very good understanding of how children learn to read and how they can best be taught. So, why shouldn't that be used in classrooms around the world?”

Over the last several years, she’s developed a collaboration with The World Bank, working alongside them to take her research worldwide. Thanks to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, over 90% of children across the world are now enrolled in primary school getting access to an education. But they’re still not learning to read, so how can they learn anything else?

Kathy’s most recent work spanned 48 countries, representing 500, 000 children. “Our research showed in the first three years of reading instruction, children in many low- and middle-income countries make almost no progress—even in recognising letters,” Kathy explains.

For Kathy, connecting with stakeholders on the ground and beyond the academic sphere is key. Being able to understand what is happening in classrooms helps her to see where to take her research next. For instance, through her recent project she discovered that around 40% of children in low- and middle-income countries are taught to read in a language they may not understand. This presents even more of a challenge because of the link between spoken and written language. “It’s a double whammy,” she says. “You might be able to decode the word ‘cat’ but if you don’t know what that word means, you can’t read.”

Her next step is to look at what they’re being taught.

“In order to design a better curriculum we need to understand how different languages and writing systems work.”

She’s just received a large grant from the ESRC to study how people read in Arabic. Despite being a major global language spoken by hundreds of millions and the national language of 24 countries, Arabic has been almost totally ignored in the science of reading. That’s an important gap to rectify because 18 of those countries are in the low- and middle-income category, where around 60% of children fail to learn to read. By understanding the mechanics of how people read in Arabic, she’ll be able to adapt the science of reading to deliver teaching methods that lead to better results.

Why it matters

Kathy is hopeful for the future.

“If we can shift the dial in these low- and middle-income countries the impact will be enormous, because of the sheer numbers of children involved.”

Through her collaboration with the World Bank Kathy’s research is reaching further than ever. In an exciting development, The Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel (GEEAP), alongside the World Bank and the Gates Foundation recently released a new paper highlighting Kathy’s research with the World Bank and endorsing using the ‘science of reading’ approach in low- and middle-income countries.

|

“For a researcher, to see that their work is impacting millions of people and altering their life chances is enormously fulfilling,” Kathy reflects. “We can actually see how our research is making a difference.” |

By taking a scientific approach and using the evidence to inform teaching methods Kathy’s research is having a major impact and helping to change lives around the world.

Discover more about Kathy's research on her Lab's homepage and hear her discuss her ideas in the video links below:

Rastle Lab: Literacy, Language, LearningExperimental Psychology Society (EPS) - 'EPS President's Address' - Kathy Rastle, July 2023

- How to use psychology research to make a difference.

Talks at Google: Kathy Rastle - Learning to read

- An accessible summary of the evidence around how children learn to read.

Return to our Research in Focus page to uncover more exciting research happening at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Research in focus